Lyndhurst: a Gothic Revivalist mansion in the romantic style, built in the ghostly pale marble of its Hudson River surroundings in Tarrytown, New York. A shimmering example of Gilded Age glamour, this former home of three successive prominent New York families was latterly that of the infamous industrialist and financier, Jay Gould, whose children, nonetheless, had a social conscience. His daughter, Helen, was a noted philanthropist and, among her many acts of benevolence, used the house to help retrain women in service to sew. Her younger sister Anna (who would become Duchess of Talleyrand-Perigord) inherited the house on Helen’s death in 1938 and, despite mainly living in France, kept it fully staffed. On her own passing in 1961, she bequeathed it and its contents to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, in which care it remains to the present day.

The sylvan waterfront setting is part of the landscape that inspired the Hudson River School, the group of mid-19th century American romantic artists, of which the young Louis Comfort Tiffany became a second generation exponent. Tiffany studied landscape painting under the tutelage of adherents George Inness and Samuel Colman and practiced a style of painting known as luminism, in which the rendering of light was paramount. Thanks to his affluent background, Tiffany was able to travel extensively throughout his teens and early twenties, and often portrayed scenes of social significance in these early paintings, illustrating a sensitivity to his own good fortune.

These youthful experiences were the jumping off point for an exhibition of Tiffany’s career that Lyndhurst mounted this summer. BecomingTiffany: From Hudson Valley Painter to Gilded Age Tastemaker, charted Tiffany’s trajectory from his early days as a young painter, to being a society decorator and wildly successful entrepreneur.

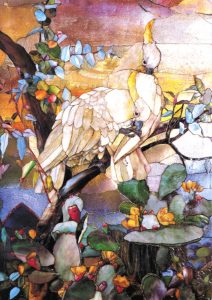

While Lyndhurst is home to many Tiffany artefacts of its own, this exhibition brought together some 50 examples of paintings and decorative works from public and private collections in the US and the UK, including two pieces from the Haworth’s own collection: its stunning iridescent mosaic of Sulphur-crested Cockatoos and its rare Aquamarine vase (both shown here).

Tiffany’s painting style owed much to the Hudson School and the luminist approach; his mentor, Colman, would become a collaborator in Associated Artists, Tiffany’s first business venture, along with Lockwood de Forest and Candace Wheeler; all highly skilled proponents of their respective crafts, testing the boundaries of art and design.

Tiffany and his cohort became a new breed of society decorator, creating works of intense beauty and intricate craft in the new, fluidly organic style that would come to typify Art Nouveau. Members of the group designed, created and installed entire rooms, sometimes entire houses, from the furniture to the lamps and vases that adorned it; from the curtains to the window panes; they were the celebrity designers of their day. During this time, Tiffany’s artistic leanings were increasingly developing toward glassmaking and he experimented with techniques to create eye-catching effects, such as his trademark iridescence.

The era of the so-called robber barons had for Tiffany the fortunate corollary of generating a demand for works of glittering beauty at almost any price and as an astute businessman, he made clients of many of his wealthy neighbours in the Hudson Valley and Manhattan.

During this time, Tiffany also secured two career-defining commissions: to decorate the Mark Twain House in Hartford, Connecticut, and to redecorate several key rooms at the White House. His strengths as a decorator and as an entrepreneur were firmly established and he would soon set up Tiffany Glassmaking, later to become Tiffany Studios, peeling off from the rest of the group. Although the associates went their separate ways, they remained on good terms throughout their careers.

Gould patronage

While some of Lyndhurst’s many stained glass windows attributed to Tiffany remain in question – and indeed Jay Gould at one point installed windows attributed to Tiffany’s main rival John La Farge – nonetheless, numerous windows, many lamps and a slew of decorative items in the house are incontrovertibly Tiffany.

What is also certain, is that Helen Gould engaged Tiffany on numerous public and private commissions. Among her own personal commissions is a 10-foot stained glass panel of a doe drinking from a stream, a biblical allegory, and a smaller replica of which was displayed in the exhibit. Only now is Helen’s collaboration with Tiffany increasingly understood to have been his key connection to Lyndhurst and it is now thought to be she who should receive credit for many of the perspicacious choices that until very recently had been attributed to her father.

Lamps both owned and loaned punctuate the house throughout with spots of colour. A particularly splendid peony lamp on loan from a private collector and almost identical to one photographed with Helen Gould sat on display in the elegant dining room; a suitably Halloween-themed spider lamp graced a hall table. A sweet green banker’s lamp of the house’s own collection gleams cheerfully in a small bedroom, as do many others, casually dotted around. Standard lamps are poised at reading height alongside elaborately carved sofas. The interiors of the house are replete with Tiffany style.

It is Tiffany’s capture of light, often through a prism of saturated colour, filtered through or reflected in glass (and occasionally enamel), that would become characteristic of his lifetime’s work and which traveled through the myriad jewel-like artworks he created; from the luminism of the early paintings to the irridescence of his tiles and vases, the translucence of his lamps and windows.

The enduring joy of Tiffany’s works shines out at Lyndhurst, as it does at the Haworth; friendly and welcoming places both, rejoicing in the bequest of wealthy industrial (and female!) benefactors.

The Sulphur-crested Cockatoos will soon be winging their way back to their home territory (as will the Aquamarine vase), where they will form part of the Haworth’s redisplayed Tiffany exhibit, highlighting the significance of Tiffany foreman Joseph Briggs’ mosaic work and his critical role in Tiffany Studios’ success. Make sure not to miss these jewel box collections, whichever side of the pond you happen to be.