Hidden Gems: The Collection of Thomas O. Chua | Christie’s

Louis Comfort Tiffany: Treasures from the Driehaus Collection | Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture | Museums, Community, Visual Arts | The Pacific Northwest Inlander | News, Politics, Music, Calendar, Events in Spokane, Coeur d’Alene and the Inland Northwest

Haworth centenary: what’s in store?

The Haworth’s centenary as Accrington’s art gallery – the jewel in the town – is just around the corner. The fascinating photograph above was taken in 1921, the year the building was opened to the public. What a decorous entourage assembled for the occasion!

As the Haworth staff and Friends volunteers prepare to mark the 100th anniversary (watch this space!), we’ve been hard at work documenting the gallery’s two major artwork stores, uncovering and preserving important artefacts in the permanent collection, many of which will help shape the event.

Our featured photograph was among the hundreds of items in the building’s watercolour store, work on which has been ongoing for the past year, documenting and assessing the condition of each item.

Among the many lovely discoveries were several sheet music albums belonging to William and Anne Haworth. At least one album, bearing William’s monogram and the date 1902, pre-dates the era when the Haworths lived in the house, then known as Hollins Hill. Friends’ member Frances Prince, leader of the Red Rose Singers, is cataloguing this music, with plans for the group to perform some of it in the 2021 anniversary celebrations. The centenary exhibition will chart the story of the house and celebrate the people who lived and worked here from 1909 to 1920.

In addition to all the fantastic photographs and artwork, the store holds a variety of paper-based works, including cartoons, architectural drawings and copies of the documents and correspondence relating to the building of the house,

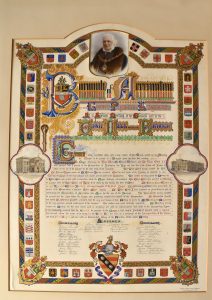

Among them was this illuminated manuscript (left), recording the bestowal of the mayoral insignia at the first meeting of the newly formed Accrington Corporation in 1878.

Also in this store is the original photograph album of the house from 1921, after Anne died and bequeathed the house to the Corporation. It shows the rooms and furnishings as they were when the house was her home. A copy of the album, sponsored by the Friends, is available at the Haworth reception desk for all visitors to see. Make sure to have a look on your next visit.

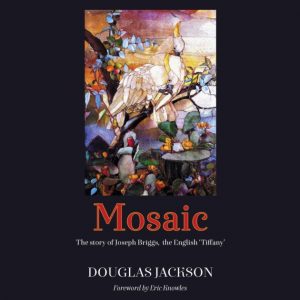

A romantic pen and ink sketch (above right) from the watercolour store suggests a Brief Encounter moment; a bittersweet image of an Edwardian-era couple, parting ways as his train prepares to leave. Also in this collection is a photographic portrait of Joseph Briggs (below right), who donated the vast majority of the Haworth’s Tiffany collection to his hometown.

In the early days of 2020, gallery staff, aided by eight volunteers, emptied the gallery’s oil store. Tasked with documenting and assessing the gallery’s more physically substantial works and re-hanging them in a more accessible order – we recorded each painting’s position in the store for ease of management.

Next on our list is documenting the Haworth’s extensive collection of art books, detailing works from Goya to Rembrandt and beyond.

Many of the works in these two stores will inform and illustrate the forthcoming anniversary exhibition, which will be a significant feature of the Haworth’s programme of events next year.

Looking ahead to 2021 has become a luminous objective. We very much hope to see you all there.

*If you’d like to help us realise any of our projects, or perhaps have information about any aspect of the gallery or its heritage – no matter how small – please don’t hesitate to contact us at haworthaccrington@gmail.com.

A Tiffany Epiphany

A (literally) brilliant benefit of being a Friend of Haworth Art Gallery: days like today when we had the privilege of Curator Gillian Berry’s insights on the Gallery’s exquisite Tiffany glass collection – and an exclusive opportunity to handle several Tiffany pieces under the strict supervision of the Haworth’s Alison Iddon. All in the sparkling winter sun of a late January day liberally dusted by frost and snow.

Gillian brought to life the story of Tiffany Studios, its personalities, and – crucially – the exquisite glass for which it became world-famous. Louis Comfort Tiffany, son of the famed jeweller Charles Tiffany, was the Studios’ founder, whose artistic vision, family wealth and marketing genius were at the core of the creative powerhouse the Studios would become. After many successful decades in business, Tiffany handed control of the Studios to Joseph Briggs, the Accrington-born engraver, who had worked his way to the top of the ladder through the roles of errand boy, mosaic maker and studio foreman for Tiffany. Joseph would later bequeath to his hometown its world-renowned glass collection.

Joseph was an accomplished mosaic craftsman, but only recently has his critical contribution to the artistic direction of the company become more fully appreciated – and the extent of his role in creating the myriad mosaics that were a major part of the Studios’ output; as foreman, he worked alongside other such formidable talents as designer Clara Driscoll (see earlier posts on Joseph and Clara). For this reason, the Haworth’s collection has been redisplayed to reflect his prominence and will continue to be adapted to respect the role he played.

A third generation engraver, Joseph was an apprentice at Steiner & Co in Accrington, where his father also worked, before leaving to seek his fortune in the States at the age of 17. Steiner, an immensely successful calico printing firm, proved to be a good training ground for Joseph; it was here that he honed his skills, engraving wooden printing blocks for the acres of Art Nouveau patterned fabrics the company sold to customers worldwide. In a wonderful piece of circularity, Joseph had initially trained at the Accrington Mechanics’ Institute, of which William Haworth (whose home, Hollins Hill, would later become Haworth Art Gallery) was a patron, and his father before him a founding member.

The dynamism of Briggs’ and Tiffany’s collaboration was astonishing and the company’s output immense. At its height, the Studios employed 540 people, many of whom were artists: designers, glass blowers, glass cutters and mosaic artists, as well as chemists. Notable among the latter, Tiffany employed Parker McIlhenny, who perfected the technique for iridescent glass that is a feature of much of Tiffany’s output. Arthur Nash, an English chemist, managed Tiffany Furnaces and was critical in helping Tiffany create the extraordinary array of colours and effects, for which the Studios became renowned, by the application of different oxides. Among their accomplishments was the ability to create degrees and styles of opalescence and translucency that could even mimic folding fabric. Often used for windows and mosaic panels, pieces were cut from large sheets of glass, production of which Tiffany brought in-house under Nash. Many such sheets remain in the vast Neustadt Collection of Tiffany objects in Queens, New York.

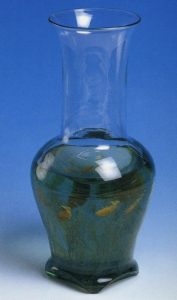

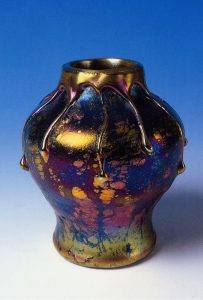

Design and experimentation in glass colours and finishes brought vibrancy to an astonishing range of vases, lamps, mosaics and windows. Iridescence became a trademark feature of various different forms of Tiffany vase, including Lava glass forms with their molten appearance (see examples pictured below). It was also sometimes used in combination with Millefiori technique, where rods of molten glass were fused to a glass form and layered over with a paper-thin sheath of transparent glass to ensure a smooth outer surface. Examples made in this way became known as Paperweight vases. Opalescent glass was also used with this technique, as seen in the elegant example above. A similar combination of techniques for decorating glass, by layering from the inside out, was used for other rare and complex pieces, such as the lifelike Aquamarine vase in the Haworth collection – one of only three known still to be in existence.

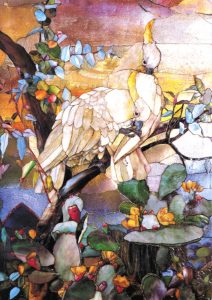

Slightly more restrained effects were created by carving opalescent glass into Cameo glass, which has a matte lustre (see the lovely blue example above). Cypriote and Byzantine styles both hark back to classical times, albeit in very different ways; Cypriote vases present a largely matte, pitted exterior, mimicking ancient amphora, while Byzantine ware is highly lustrous and formal in style. Opalescent glass also featured in many Tiffany mosaics and windows in opaque, semi-opaque and translucent forms. The breathtaking mosaic of Sulphur-crested Cockatoos pictured above – a key element of the Haworth’s collection that is often sought for loan by museums internationally – illustrates many of the impressive range of effects and colours Tiffany managed to achieve.

Great marketer and entrepreneur that he was, Tiffany adopted and trademarked the term ‘favrile’, a derivation of the old English word ‘fabrile’, meaning hand-wrought, to describe the hand-crafted nature of the company’s creations. Although an accomplished artist himself (Tiffany moved from painting to the medium of glass because of its ability to bounce light around) it is unlikely – ironically – that Louis Comfort Tiffany personally created any of the pieces for which his company became world-famous. Notwithstanding, he was the mastermind behind the company, and thanks to him – and critically to Joseph Briggs – we have this stunning collection on permanent display in sunny Accrington!

The Friends would like to thank the gallery staff for the unique opportunity of this lovely event. Next time you visit the Haworth, be sure to take time to appreciate the delicate beauty and amazing variety of this precious bequest.

If you’d like to join the Friends and take part in future activities, please contact us via haworthaccrington@gmail.com

Tiffany on Tour and a House Fit For a Duchess

Outside the Box

Throughout the summer, the Haworth staff have been working hard to manage the redisplay of the world-famous Tiffany glass exhibition. The display is being reimagined to illustrate more closely how the town came to own such a major collection of works by New York’s famed Tiffany Studios; itself an unexpected turn of events.

In fact, you could say the Haworth embodies the unexpected: an elegant Arts & Crafts mansion in a hard graft northern town; a venerable museum and art gallery where you can enjoy a Sunday rock concert; an oasis of art and culture where kids can come and get messy – and everyone can fill their boots with a lush lunch. But perhaps the biggest contradiction of all: an internationally important collection of American art glass . . . in Accrington!

How did a stunning collection of American Art Nouveau come to be in a small industrial town in Lancashire? Accrington’s many exports to New York, the products of its textile and manufacturing industries, famously include the ‘Nori’ brick core of the Empire State Building. But how did the Big Apple give up so many treasures to Accrington?

Its history follows that of a migrant Accrington lad and is a touching tribute to his hometown. The story of Joseph Briggs and his journey to New York is a significant piece of the exhibit’s provenance, and one which curator Gillian Berry felt merited closer attention.

Briggs, an engraver by training and a creative soul, was uninspired by the prospect of industrial working life in Lancashire and left for New York at the tender age of 17. His early experience in his adoptive home was far from humdrum. Through chance encounters, he spent his first couple of years in the US performing in a Wild West show; a far cry from Accrington factory life!

But Briggs’ ambitions lay elsewhere and he sought out work that would utilise his artistic skills. As luck would have it, Tiffany Studios was looking to hire new talent. Tiffany Studios was a dazzling nexus of artistic creation that captured the era’s zeitgeist and energy; exactly where Briggs wanted to be. Sadly, after a couple of applications, he didn’t make the cut. However, his artful perseverance (and perhaps a bit of northern nous) ultimately succeeded in winning him a place as Louis Comfort Tiffany’s right hand man – quite literally.

Briggs earned his 1893 entree to the company by a chance encounter in the rain, when the Englishman deftly accompanied Tiffany from his car to his office under his trusty umbrella, and forged an instant connection. After an initial trial, for which he depicted a religious scene in order to demonstrate the range of his skills, Briggs was hired. In time, he would be promoted to run the company’s mosaics department, ultimately becoming Managing Director of the studios and remaining for some 40 years. Briggs’ association with Tiffany was unique; both had maverick and creative streaks that they understood in each other. and the two worked very closely to the great benefit of the company.

Briggs had the overseer’s task of winding up the studios and their contents. In so doing, his mind returned to his hometown. He arranged for a large trove of some 140 Tiffany treasures to be sent back to Lancashire, where they were gifted to the town of Accrington Sadly, Briggs’ own demise not long afterwards, meant that his gift became his personal legacy to his native town.

The collection was placed in safe storage during the Second World War and languished unappreciated in boxes and crates for many years. But in the 1970s, the glass found its way to the Haworth and, happily for the viewing public, has been on display there ever since; an awe-inspiring representation of artistic and human endeavour. The collection is perfectly at home in the sympathetic surroundings of Walter Brierley’s Arts & Crafts architecture; the house and the collection each being wonderful examples of their respective turn-of-the-Century design schools.

The new reconfiguration of the Tiffany exhibit at the Haworth will illustrate the journey of these astonishing artefacts and highlight their connection – the great gift of Joseph Briggs and his part in Tiffany Studios’ success – to the town they now call home. Briggs’ own interest and prowess in mosaic-making will be brought to the fore and the flow of the exhibit will emphasise this creative process and its significance within the collection. It’s sure to be a fresh and fascinating approach to this stunning exhibit.

Stay posted for news of the display’s reveal and whatever you do, don’t delay – come see for yourself!

Fresh light on spring blooms: Clara Driscoll and the ‘Tiffany Girls’

Spring bulbs in bloom, branches heavy with apple blossom, trailing racemes of laburnum and wisteria, each illuminated in stunning clarity, as vivdly as in nature. The bright botanicals of Tiffany lamps are a phenomenon of design, but the little-known history behind their creation is equally astonishing.

While Louis Comfort Tiffany was always the marquee name at the forefront of Tiffany Studios (and a carefully maintained brand image), much of Tiffany’s creative work was carried out in anonymity by a large team of designers and artisans. Although the Tiffany staff was largely male, women soon became a key part of the workforce. From 1892 onwards, a critical part of of the cohort comprised a creative powerhouse of women: the self-annointed ‘Tiffany Girls’. They worked in the Women’s Glass Cutting Department, a separate division within the otherwise male design team. The department was led by a remarkable woman whose artistic talents played an enormous but publicly underrepresented role in the company’s prodigious output.

Clara Driscoll, a skilled designer and artist in glass, created many of the company’s most beautiful and innovative designs, including iconic dragonfly and wisteria lamps, striking peony and poppy lamps and various other floral filigree lamp designs illustrated here. In fact, according to recent research detailing the history of Driscoll’s influence and the work of the women designers: “It was possibly Clara who hit upon the idea of making leaded shades with nature-based themes,” A major element of the Tiffany brand.

Clara counted many skilled and artistically adventurous women among her team, including Agnes Northrop, another talented and prolific designer, but the demands of the work meant that it was not a job for any artist, regardless of her abilities. As inconceivable as it may seem in our times, women could only be employed at the Studios if they were single. Clara was obliged on two separate occasions to leave her job, the first of which when she was engaged to be married. She returned to work after the untimely death of her husband, but left again when she became engaged for a second time. This engagement ended in the mysterious disappearance of her fiancé and Clara’s ensuing third term at Tiffany was her longest and most prolific. During this time she was also responsible for managing the now sizeable department of some 35 women.

Continue reading “Fresh light on spring blooms: Clara Driscoll and the ‘Tiffany Girls’”

Tiffany Turtleback Over the Pond

A delightful visit to the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian’s Design Museum in New York to mark its acquisition of a Tiffany turtleback chandelier from Macklowe Gallery Housed in the former New York city mansion home of Scottish financier and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, the museum has formally acquired this fine example of a Tiffany pendant lamp for permanent display in its recently restored Teak Room.

As the home’s former library, the Teak Room is the most intact of the Carnegies’ family rooms. On the first floor (second if you’re American) of the mansion, it is a burnished cocoon of a room, a sanctuary where the family could relax away from the house’s more public lower floor. Decorated by artist and interior designer Lockwood De Forest in the Arts & Crafts idiom, it is inspired by his infatuation, and that of his contemporaries, with Indian design and craftsmanship. Its ceiling’s filigree pattern depicts a bramble of interwoven branches against a field of lacquered ochre. The gleaming golden light of the chandelier illuminates both the ceiling and the lustrous red-gold sheen of the stylized floral wall coverings to subtle effect. Continue reading “Tiffany Turtleback Over the Pond”